Appendix 2

- Task

- Practice Exercises

📚CLIL ACTIVITIES#

(from “CLIL Skills by Liz Dale, Wibo van der Es, Rosie Tanner”)

PRACTICAL LESSON IDEAS - ACTAVATING #

1. Key words#

| Guess the topic of the lesson and explain useful words. |

Write ten random key words about a topic on the board. Ask learners to answer these questions:

|

| Biology: Classification Write the words kingdom, class, family, species, genus and phylum on the board: Ask learners to guess what the lesson will be about, and whether they can add any more words related to this classification. Then ask them to look up and note down a definition for one word. In turns, learners read aloud their definition and everyone writes down which word is being described. |

2. Competition. Quickest or most#

| Quickly list a fixed number of words or produce as many as you can, related to the topic of the lesson. |

Write the topic of the lesson on the board. Learners work in pairs to either

|

| Geography: Global warming Quickest Ask learners to work in pairs and write down ten verbs used to talk about global warming. Which pair is the first to get ten? Most Give learners one minute to write down as many verbs used to talk about global warming as they can think of. Which learner produced the most in the time available? |

3. Questions#

| Write down ten questions about the lesson topic. |

| Write the topic of the lesson on the board. Learners work in pairs and write down ten questions about the topic - at least four should begin with who, what, how and why. |

| History: The slave trade Ask learners to write down ten questions they would like to have answered about the slave trade. They might produce questions like:

|

4. Scrambled sentence#

| Mix up the words of a sentence about the topic and ask learners to re-create the original sentence. | ||

| Choose one sentence or question which is relevant (humorous, interesting, controversial) to your topic and mix it up. Write the scrambled words on the board, or create small cards – one word per card. Ask the learners to create one sentence from your mixed up words. If it is a question, you can ask for their answers and discuss these. | ||

| Science: Nuclear power Scramble the sentence: Nuclear power is the most environmentally friendly means of generating energy. | ||

| Nuclear the energy. means | environmentally power friendly | is most of generating |

| Ask learners to recreate the sentence. Once they have completed that task, they discuss how science might prove or disprove this claim. You can scramble a paragraph or complete text, too. Make cards or a handout of the mixed-up sentences or paragraphs and ask the learners to reconstruct the text or paragraph. | ||

5. Red and green cards#

| Decide if statements about a topic are true or false. |

| Create a list of ten true and false statements about a topic you are going to cover. Each learner receives one red and one green card. Read your true/false statements out one by one. The learners each decide if the statement is true (green card) or false (red card). Once the statement has been read out, they hold up a green or red card. After each statement, you can either discuss their answers, or leave them unanswered and repeat the activity once the lesson is over to check what they have learned. This activity can also be done with agree/disagree statements, for example if you are discussing an ethical topic. |

| Physics: Solids, liquids and gasses Read out these statements:

|

6. Props or visuals#

| Ask questions about objects or pictures connected to the topic. |

| Bring in and display a number of objects or visuals related to the lesson. |

| Art and design: The construction of pop-up cards Props Show learners four examples of pop-up cards and ask them questions, such as “Which do you like best and why?”, and “Which would be the easiest and/or most difficult to make and why?” Visuals Select an intriguing picture, cartoon or photograph of an optical illusion. Make enough copies for everyone, or use a smart board or data projector. Ask learners to identify the techniques that create the optical illusion. You can find examples of optical illusions at www.yourdailydump.com/category/optical-illusion |

7. Video clip#

| Watch a short video clip related to the topic and answer questions. |

| Search for a video clip related to your concept or topic on YouTube or elsewhere on the Internet to show to your learners. Give them some viewing questions beforehand. Discuss the questions afterwards. |

| Social Studies: Gender differences Learners watch the clip (a comedy sketch about the effect of education on men and women) and list which differences between men and women are emphasised in the clip. Women: Know Your Limits! (Harry Enfield) |

| Biology: Homeostasis and the pancreas Learners watch the clip. While watching they write down what the pancreas does and why it is an important body part. Weird Al Yankovic: Pancreas Song |

8. Internet#

| Learners find information on the internet individually about a topic before the lesson and then sort all the information they have found into categories. |

| For homework, ask learners to bring an image or a text they have found on the Internet about the topic you are going to cover in the lesson. At the beginning of the lesson, they pool all the images or texts and then categorise them. |

| History: Spanish occupation of the Netherlands Ask learners to find a 50-word text about or an image of the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands and bring a copy to the lesson; their copies need to be large enough so that they can be read at the back of the classroom. As they enter the classroom, learners stick their texts or images on the board with tape and sit down. In pairs, the learners then look at the ideas and/or images on the board. Their task is to think of four or five main categories into which all the texts and/or images could be placed. |

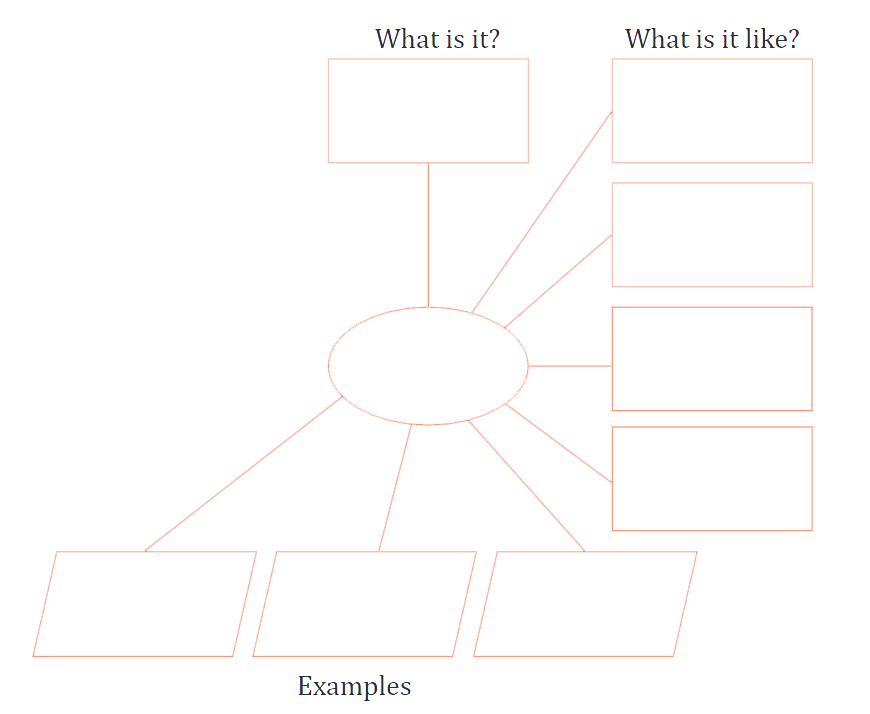

9. Spider diagram#

| Create a mind map of useful words for a topic. |

| You can do this in two stages; first ask for as many associations as possible, and then ask learners to put all the words into categories. Once learners have made a number of spider diagrams, they can create them by themselves or in small groups. Choose a main concept related to the material you want to cover. Place it in the middle of the board in a circle or square. Ask learners to call out sub-topics related to your main concept. Together, create a spider diagram related to the topic, with each leg of the spider relating to a sub-topic. |

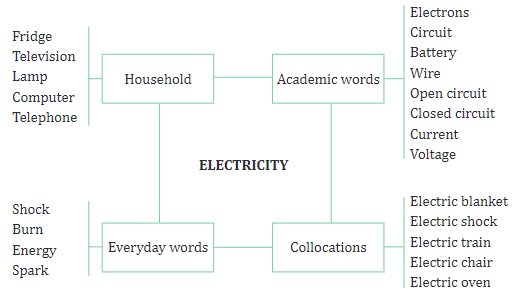

Physics: Electricity |

10. KWL grid#

| Learners list what they know, want to know and have learned about a topic. | ||

| Learners complete the three columns of the KWL (know, want, learn) grid. In the first column, they write what they know; in the second column what they want to know. The third column is for summarising what they have learned at the end of the unit. To use this activity effectively and focus the learners, it is important that the desired final product is clear: it is hard to complete a KWL grid without an explicit aim. | ||

| History : Project making a newspaper article dated somewhere in the autumn of 1939 | ||

| Know Start of WW2 First year of war Germany involved | Want Where is our story? Who was involved? What was happening? Countries involved? Famous people Role of Netherlands | Learn |

11. Placemat#

| Learners write ideas about a topic individually and then compare and combine their ideas. |

| Make groups of four. Learners sit around a table with a large sheet of poster paper in front of them and a marker each. First ask the learners to draw a ‘placemat’ on their paper, like this: Round One Provide the learners with a question or issue. Write this in the middle of the placemat. Each learner then writes a comment or opinion in their own space on the placemat. Round Two The learners read what the others have all written (by turning the placemat around) and discuss a ‘sponge’ question. This is a question which aims to combine or categorise the ideas from Round One. It is important to have a fresh question at this stage which further processes the ideas from Round One. |

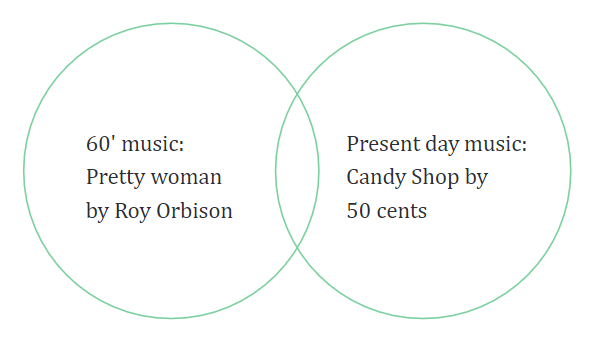

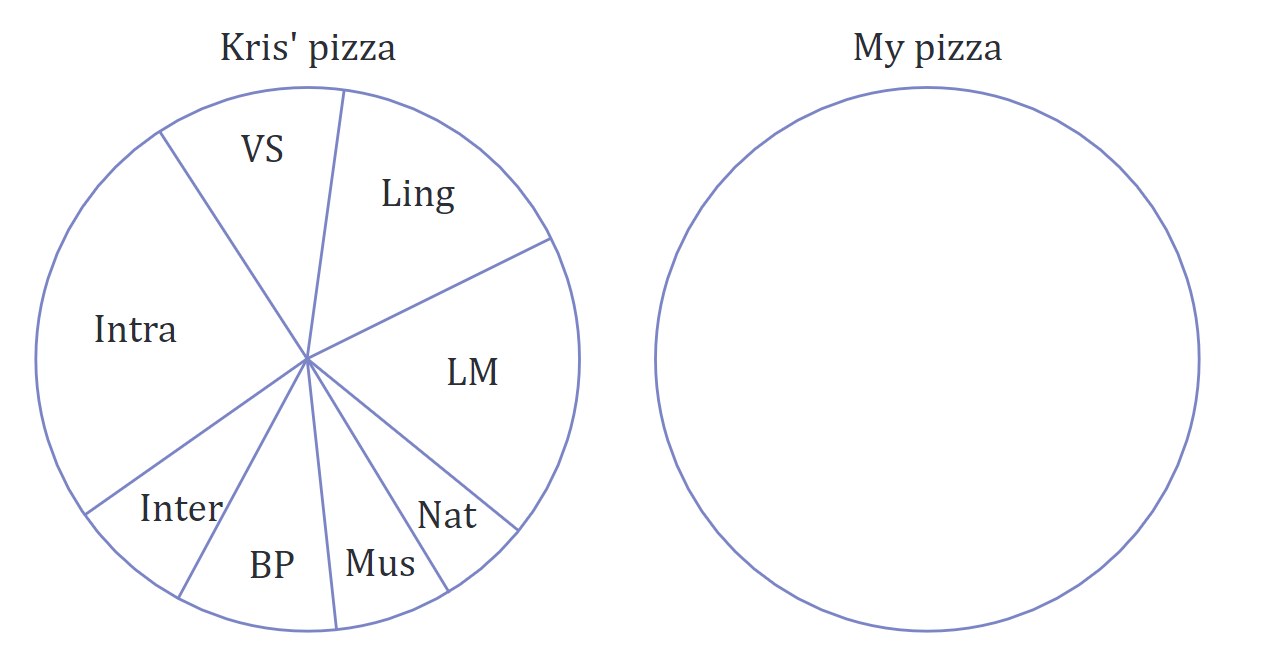

12. Venn diagram#

| Complete a Venn diagram about a topic. |

| A Venn diagram is an excellent tool for activating prior knowledge in order to highlight similarities and differences. Learners write the two topics to compare in the circles, and then write similarities between the topics in the middle (overlapping) space, and differences in the outer spaces. |

| Music: 60’s and 90’s songs Provide each pair of learners with an empty Venn diagram on a sheet of paper. Choose two songs which the learners know to compare. They write the title of Song 1 in the left circle, the title of Song 2 in the right circle. Ask them to write similarities and differences between the two songs.  |

13. Think, pair, share#

| Learners answer a question first individually, then in pairs and then share their answer with the whole class. |

| Think, pair, share is a simple technique which gets everyone thinking about a topic. Individually, each learner writes down their answer to a key question (on language, knowledge or content) provided by the teacher. This gives them some time to think for themselves. Next, in pairs, learners compare and discuss their answers with each other. Finally, have a short plenary discussion of some of the groups’ answers. |

| Geography: Earthquakes Key question: What do you think causes earthquakes? Or: Why do earthquakes happen? Music: Rap music Key question: What do you think are the characteristics of rap music? Or: What is a rap song? For example, think about beat, background, topic, story, rhyme and refrain. |

14. Predict, observe and explain#

| Present an event and ask learners to predict what they think is going to happen, then watch what actually happens and explain why they were right or wrong. |

| In a predict, observe and explain sequence, your learners are expected to predict the outcome of an event or experiment, observe what actually happens and then explain why their prediction was either right or wrong. This activity is best suited to science classes. It can be an individual assignment or a small group activity. The aim is not only to activate prior knowledge but also to promote personal involvement of your learners. |

| Science Some interesting examples of cartoons used for predict, observe and explain activities can be found here: http://www.conceptcartoons.com/science/examples.htm. |

15. Sentence stem#

| Learners complete a sentence about a topic. |

| The learners have to complete the sentence in as many different ways as they can. The follow-up can be a Think, pair, share or Placemat activity. |

| Think of a ‘sentence stem’ which can be completed in various ways related to an aspect of your topic. Write the stem on a worksheet or the board ten times. Use a sentence stem that learners can easily complete; nothing too difficult. For example: Shakespeare.... Shakespeare.... Shakespeare.... (etc.) Geography: Deserts The desert is... Biology: Cells Cells... |

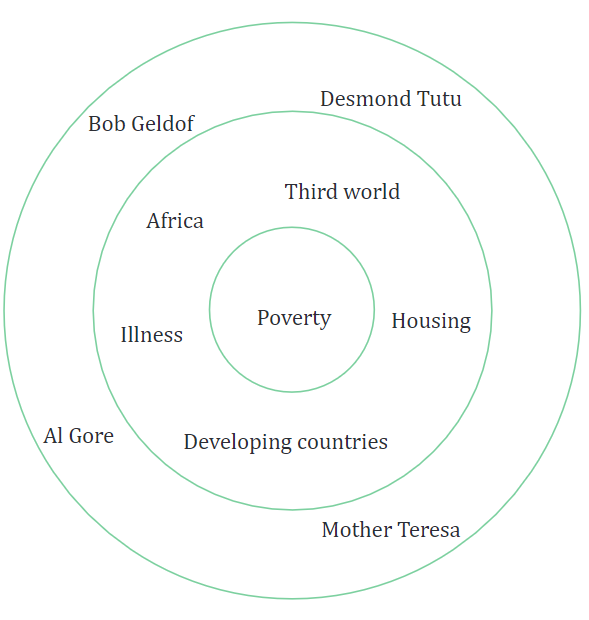

16. Target practice#

| Learners complete a target image with ideas and people related to a topic. |

| Provide a handout of a target for each learner, with the lesson topic in the centre of the target. In the second, slightly larger circle, learners brainstorm about the topic. In the outer circle, they write down the names of people who might have influenced thinking related to the topic (either their ideas or the topic in general). |

Social studies: Poverty |

PRACTICAL LESSON IDEAS – EVALUATING INPUT #

17. Finding materials online#

| Provide varied resources and materials for input. |

| A Smart Board, computer room or data projector linked to a computer provides a great opportu- nity for providing varied online input. Here are some of our favourite resources for varied input. |

| Video clips YouTube This well-known site offers short video clips on many subjects. A search for ‘great depression’ reveals some vivid photographs from the time of the great depression, backed by music from that period (e.g. ‘This land is my land’). A search for ‘chemical reactions’ produces a motivating educational video on alkali videos with chemicals exploding in a bath. Spoken text iTunes The iTunes store has free downloadable podcasts of great speeches in history, such as Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’, or J.F. Kennedy’s inaugural speech. There are many podcasts on historical, scientific or cultural topics, too. Educational documentaries TeachersTV TeachersTV offers a wealth of educational documentaries. These have been categorised by subject (English, ICT, maths and science) and level (primary or secondary school). Written and spoken input How Stuff Works This site is a goldmine of information on many school topics, with clearly-written texts backed by visual material such as photographs and videos. Online news resources Many teachers like to link their work in the classroom to topical subjects. Try using: Visuals Google Images Use Google images to find photographs or other visuals for your lessons. The larger the image, the better the quality. For example, pictures measuring 400 x 300 pixels are not as good as ones that are 600 x 800. Through Advanced Search, you can further refine your search (cartoons, black-and-white only, etc). Visuals Google Earth “Google Earth lets you fly anywhere on Earth to view satellite imagery, maps, terrain, 3D buildings and even explore galaxies in the Sky. You can explore rich geographical content, save your toured places and share with others”. Lyrics Lyrics search engines Although heavy with advertisements, these sites provide lyrics to most well-known songs. Songs for teaching: www.songsforteaching.com Here you can find songs for different school subjects. |

18. Graphic organisers#

| Help learners organise and understand new vocabulary or concepts. |

| Provide a note-taking structure - or graphic organiser - for learners to complete as they work with the input. For more difficult input, you can provide partially-completed organisers which learners complete further. |

| A good website to start is http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/think/articles/graphic-organisers |

19. Using pictures and asking questions#

| Support texts with visuals or hands-on activities. |

| Select a visual - a photograph, cartoon or other image - which is strongly related to your topic. Then create a task around the visual to introduce your learners to the lesson topic and get them talking. Make sure that all the learners can see the visual. You might use a list of questions, a pile of cards with questions, or a mind map to complete. First ask the learners to think about it in pairs, and then discuss some ideas together in plenary. |

| Physics: radiation When showing an image of people wearing a hazmat suit (garment worn for protection against hazardous substances), you could ask the following questions: What, where and when? What is the photo of? Where was the photo taken? |

| When (time of day, or year) was the photo taken? Write down two questions you would like to ask about the photo. Think of a catchy title for the photo. Who? Who is in the photo? What are the people doing in the photo? What are they wearing/What do they look like? What is the relationship between the people in the photo? Who is the photographer? Why? Why do you think the photograph was taken? Who or what event was the photograph taken for? What is the photographer trying to convey to the viewer? In-depth If this photo was the cover for a book, what would the title of the book be? If it were a CD cover, what kind of music would it be? What might the title of the CD be? If the photo was illustrating an article, what would the title be? What do you think the message of the photo is? |

20. Interview#

| Encourage spoken input. |

| Before you start a topic or provide some input, ask your learners to interview a person or people (preferably in English) about the topic. For example, they might interview a grandparent, elderly relative or neighbour about their experiences during the war, or an acquaintance about their job or thoughts about a topic in the news. |

| History: World War II Provide an interview framework like the one below, ensuring you leave enough space for learners to enter the answers. Learners can also create their own framework. Interview framework about the Second World War First, ask your interviewee if you may ask them some questions about themselves and their experiences during the war. Write the answers to their questions on this form. My name Name of person I interviewed Date of birth of person I interviewed Date Interview Questions

|

21. Hands-on experiments or experiences#

| Support texts with visuals, hands-on activities or experiments. |

| Visualise your content with real objects, hands-on experiments or experiences. In this way, learners can reinforce their learning through a non-linguistic channel. Concrete vocabulary can be visualised through objects, and an experiment carried out at the start of a lesson can aid later understanding |

For some ideas, see:

|

22. Mind the gap#

| Make a gapped text. |

| Select a dozen or so important words from your input which you would like learners to understand and eventually use. Make a gapped text (cloze test) of your input, providing the words to fit into the gaps. Ensure the gaps are numbered for easy reference later and that they are not too close together, so that learners can use the context of the text to guess the words. You can make it more difficult by providing extra words which do not fit the text, or easier by providing dictionaries. This task actively engages learners with the important concepts of a unit. |

| Technology: how SMS works Below is an excerpt from a text entitled ‘How SMS Works’ (adapted from https://computer.howstuffworks.com/e-mail-messaging/sms.htm). There are 10 numbered gaps in the text. Can you complete the gaps with 10 of these words? |

| SMS text messaging cell phone sending cell phones text message characters short message service handling cells control channel receiving Introduction to How SMS Works ust when we’re finally used to seeing everybody constantly talking on their 1 ______ __________ it suddenly seems like no one is talking at all. Instead, they’re typing away on tiny numerical pads, using their 1 ________________ to send quick messages. SMS, or 2 ________________, has replaced talking on the phone for a new “thumb generation” of texters. In this article, we’ll find out how text messaging works, explore its uses and learn why it sometimes takes a while for your 2 ________________ to get to its recipient. SMS stands for 3 ________________. Simply put, it is a method of communication that sends text between 1 ________________, or from a PC or handheld to a cell phone. The “short” part refers to the maximum size of the text messages: 160 4 ________________ (letters, numbers or symbols in the Latin alphabet). For other alphabets, such as Chinese, the maximum SMS size is 70. 4 ________________. But how do 5 ________________ messages actually get to your phone? [...] Even if you are not talking on your cell phone, your phone is constantly 6 ________________ and 7 ________________.information. It is talking to its cell phone tower over a pathway called a 8 ________________. The reason for this chatter is so that the 9 ________________ system knows which cell your phone is in, and so that your phone can change 10 ________________ as you move around. Every so often, your phone and the tower will exchange. a packet of data that lets both of them know that everything is OK. Key: 1. cell phones; 2. text message; 3. short message service; 4. characters; 5. SMS; 6. sending; 7. receiving; 8. control channel; 9. cell phone; 10. cells |

23. Word cards#

| Help learners understand new words through categorising. |

| Before you provide input, copy 20-30 words related to your input onto as many cards. The words should be related to three or more sub-topics. Give a set of cards to a pair of learners and ask them to categorise the words according to the sub-topics. This will help them (and you) to see which words they already recognise and understand and which are new. |

| Biology: bones, organs and other parts of the body Bones: clavicle, skull, scapula, humerus, radius, cranium, spine, femur, patella, sternum Organs: heart, stomach, kidneys, intestines, skins, lungs, pancreas, kidney, liver, eyeOther parts of the body: quadriceps, oesophagus, th roat, triceps, windpipe, platelets, gluteus, anus, vein |

| Chemistry: divide words into the three categories of liquids, gasses and solids. |

24. Word cards 2#

| Help learners to recognise and understand vocabulary. | |

| This activity should be used with input that uses many word combinations or collocations.Put one half of each collocation on a coloured card, and the other half on a different-coloured card. Mix the cards up. Give each group of learners two sets of cards. They then try to find the correct collocations. Once they are done, they can guess the topic of the lesson that is to follow. | |

| Biology: health | |

| Pink cards | Blue cards |

| black | eye |

| sprained | ankle |

| allergic | reaction |

| heart | attack |

| heart | beat |

| blood | pressure |

25. Spot the words#

| Help learners to notice language. | |||||

| Make a list of verbs, nouns or adjectives. Add six words which are not in the same category. Ask learners to find the words which do not belong to the category. | |||||

| Biology: endangered animals An adjective is a word that describes a person, animal, place, thing or idea. Adjectives modify or ‘give more information’ about nouns, e.g. a beautiful dog. Which of the following words are not adjectives? | |||||

| Cross out these non-adjectives and add more adjectives of your own. | |||||

| spotted | lovable | quick | moist | territorial | ears |

| furry | vicious | warm-blooded | cute | dry | shiny |

| long | wild | cold-blooded | adorable | shy | small |

| striped | tame | heavy | rough | dominant | large |

| deadly | diurnal | aggressive | scaly | submissive | nocturnal |

| soft | hairy | wings | patterned | maternal | cat |

26. Make a gapped text#

| Help learners develop reading strategies. | ||||||||

| To help learners develop reading strategies, blank out the new vocabulary or keywords in a text and see if they can understand without these. | ||||||||

| Science: cloud in a bottle Cloud in a bottle: How does it work? (Adapted from https://www.stevespanglerscience.com/experiment/00000030). Even though we don’t see them, water molecules are in the air all around us; it’s called water 1 ____________________. When the molecules are 2 ____________________ around in the atmosphere, they don’t normally stick together. Squeezing the sides of the bottle forces the molecules to squeeze together or 3 _____ _______________. Releasing the pressure allows the air to 4 ____________________, and in doing so, the temperature of the air becomes cooler. This cooling process allows the molecules to stick together more easily forming tiny 5 ____________________ and clouds are nothing more than tiny water 5 ____________________. The smoke in the bottle also helps this process. Water particles will group together more easily if there are some solid particles in the air to act as a 6 ____________________. The invisible particles serve as the 6 and help in the formation of the cloud. Clouds on Earth form when warm air rises and its pressure is reduced. The air 7 ____________________ and cools, and clouds form as the temperature drops below the 8 ____________________ point. The invisible particles in the air may be in the form of pollution, smoke, dust or even tiny particles of dirt. | ||||||||

The blanked-out words are:

|

PRACTICAL VOCABULARY IDEAS #

27. Odd one out#

| Decide why a word does not fit in a group. |

| Create groups of 4-5 words or concepts related to a topic you have already covered. Ask the learners to discuss in pairs or groups which word is the odd one out. There should be no easy right answer or obvious word that doesn’t fit. The learners should have to think quite hard and argue their point in order to discover their own odd one out. |

| Economics: money Fares, fees, price, money Fortune, treasure, wealth, money Lend, hire, lease, borrowReceipt, bill, tip, note |

| Chemistry: plastics Styrofoam, polystyrene, PVC, Teflon, Saran Mould, melt, scorch, recycle, bendInert, raw, brittle, hard, heavy Gum, rubber, plastic, nylon, vinyl |

28. Word cards#

| Sort words on a topic into sub-categories. |

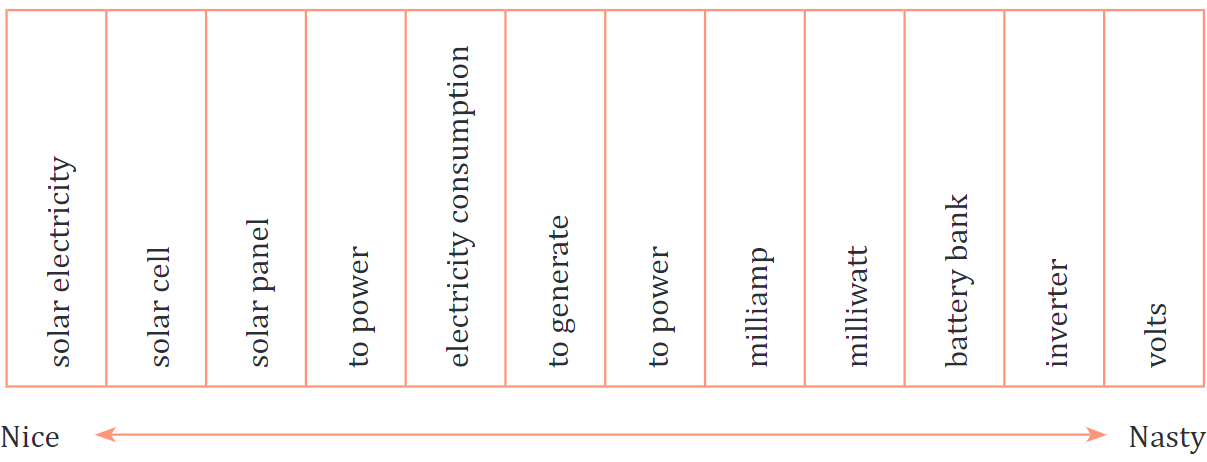

| Choose 20-30 words related to a topic you are covering that you would like to emphasise or recycle. The words should be divisible into three or four categories such as related sub-topics (biology - bones, organs and other parts of body) or other types of sub-topics (colours, shapes, a continuum). Write all words in a jumble on the board. Learners categorise the words on a hand-out or in their notebooks. |

| Geography: China Physical geography: steppe, desert, Tien Shan mountains, Himalaya, plateau, Taklimakan desert, Yangtze river, Yellow River, typhoons, bamboo Economy: terrace, commune, irrigation project, silk, rice paddy, water buffalo, heavy industry, special economic zones, mining, yuan Culture: Mandarin, Confucianism, one child policy, Han, ethnic minority, Cantonese, Buddhism, Taoism, Cultural Revolution, politburo |

| Economics: banking We have come across the words below during our lessons over the past few weeks. This task will help you to remember them better. Account, bank, statement, borrow, budget, cash, cashier, cheque, credit card, currency, deposit, savings, withdraw, instalments, receipt, refund, income, pay into, save up, take out, broke, hard-up 1 Write each word under the colour you associate it with. For example: |

| Biology: five senses We have come across the words below during our lessons over the past few weeks. This task will help you to remember them better. colour blind, listen, tongue, bitter, hard of hearing, tickle, glance, stroke eye, glimpse, rub, look at, notice, stare, hear, eyesight, scent, stink, sniff, aroma, nose, inhale, mouth, sweet, deaf, sour, taste buds, feel, ear, massage, blind. Write each word under the sense you associate it with. Possible key Hearing: hear, listen, deaf, hard of hearing, ear Sight: glance, eye, glimpse, look at, notice, stare, colour blind, eyesight, blind Smell: scent, stink, sniff, aroma, nose, inhale Taste: mouth, tongue, sweet, sour, bitter, taste buds Touch: feel, stroke, tickle, rub, massage |

| Physics: energy We have come across the words below during our lessons over the past few weeks. This task will help you to remember them better. Write the words on the continuum between Nice and Nasty, according to your own opinion. solar electricity, volts, milliamp, milliwatt, to generate, to power, battery bank, inverter, electricity consumption, power grid, solar cell, solar panel  |

| Biology: blood vessels This activity is useful for topics where sub-topics have three or four different characteristics. Use it at the end of a topic to revise what learners have learned. 1. Make a table containing your chosen topics and their characteristics. 2. Copy the table you have created onto different pieces of coloured cardboard, one colour for each group of learners. Cut out the cards and shuffle them. 3. Learners form groups of four. Each group is given a pile of shuffled cards (of a single colour). Tell them they have 10 minutes to arrange the cards into three logical columns on their table. 4. You circulate, asking critical questions and giving hints about the choices learners have made. 5. Learners should be encouraged to use English only and to explain to each other why they think a card belongs in a certain column. 6. After 10 minutes, the groups rotate. Each group moves to another table and has another 5 minutes to correct or reorganise the work of another group. 7. The groups return to their original table and try to discover the changes the other group made to their work. They reorganise the columns again, depending on whether they agree or disagree with the new order. 8. If learners get stuck, you can scaffold learning by providing a short text about the three topics. 9. Discuss the correct answers with the whole class or with individual groups. 10. The columns can be arranged to produce a table of properties (for example, of the three types of blood vessels) that can be copied into notebooks for revision. Arteries: carry blood away from heart; blood at high pressure; no valves; thick muscular walls; no substances leave or enter vessel; pulse created by heart pumping & contraction of wall muscle; strong walls; carry oxygenated blood (with one exception) Capillaries: carry blood through tissues and organs; blood at low pressure; no valves; very thin walls for escape of fluids; exchange of substances with tissues; no pulse; walls delicate and easily broken; carry mix of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood Veins: carry blood towards heart; blood at lowest pressure; valves to stop blood flowing back; thinner walls with less muscle; no substances leave or enter vessel; no pulse; walls flexible & squashed easily so blood pushed further along vessel; carry deoxygenated blood (with one exception). |

29. Everyday, academic and subject language#

| Decide which words are more academic and which are more everyday language. |

| Ask learners to organise words and phrases into a table to show the difference between everyday language, subject language and academic language. |

| Biology: homeostasis Ask the learners to put these words under the right column in a table with the following columns: Everyday words, Academic words, Subject (biology) words. glucose, keeps, is maintained, sugar, inhibits, stops, rapid, quick, endocrine, hormones, release, blood, thermostat, bloodstream, secrete, pancreas, eating, sugar molecule, blood sugar level, insulin, cell, liver, internal, homeostasis, metabolism, let go, digestingHere is a suggested key; others answers are possible (e.g. blood could also be seen as a subject word). Everyday words: blood, eating, keeps, let go, liver, quick, stops, sugar Academic words: digesting, is maintained, inhibits, internal, rapid, release, secrete Subject (biology) words: bloodstream, blood sugar level, cell, endocrine, glucose, homeostasis, hormones, pancreas, insulin, sugar molecule, metabolism, thermostat It is possible to add a second step to this activity to emphasise the difference between academic and everyday language: ask learners to think of synonym pairs (quick - rapid; release - let go). |

30. Crossword#

| Complete a crossword puzzle. |

| After a number of lessons around a topic, choose the words which are important for learners to retain and create a crossword with those words. This is easily done online. |

| Chemistry: the Periodic Table |

This crossword, which revises elements in the periodic table, was made with Puzzlemaker http://puzzlemaker.discoveryeducation.com/CrissCrossSetupform.asp |

31. Mnemonics#

| Create a mnemonic to recall vocabulary. |

| Remind the learners of a series or number of words which they need to remember in sequence. Provide or ask them to invent a mnemonic to help them recall the vocabulary. |

| Chemistry: atoms which pair up N (Nitrogen), H (Hydrogen), Cl (Chlorine), Br (Bromide), I (Iodine), O (Oxygen), F (Fluoride) Mnemonic: Never Hit Clara’s Brother Immediately On Fridays Biology: classification Kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species Mnemonic: King Philip came over for green spaghetti. |

32. Gapped text with academic words#

| Complete a text which includes gaps for academic words. |

| The AWL Gapmaker: www.nottingham.ac.uk/~alzsh3/acvocab/awlgapmaker.htm.This online programme creates a gap filling exercise using the Academic Word List. Type or paste your text into the box on the site, select the sublist level (1-10) that you want to use and submit your text. This returns a new text with words from the selected levels of the AWL replaced by a gap. |

| Technology: smartphones This gapped text about smartphones was produced in about one minute. Original source. Gap File produced at level 6 Unlike many cell phones, smartphones allow users to install, configure and run applications of their choosing. A smartphone offers the ability to conform the device to your particular way of doing things. Most standard cell-phone software offers only limited choices for re-configuration, forcing you to adapt to the way it’s set up. On a standard phone, whether or not you like the built-in calendar application, you are stuck with it except fora few tweaks. If that phone were a smartphone, you could install any compatible calendar application you like. Missing words: traditional, individual, minor |

PRACTICAL ACTIVITIES RELATED TO TEXTS #

33. Noticing#

| Helping learners to notice language features in a content text. |

| Use a text which includes a particular language feature. First, discuss with learners why it is used in this particular text. Then ask them to highlight or underline the particular language feature. At a later stage in your topic, you can provide tasks in which learners complete gap texts for themselves. Either suggest possible words yourself or, for more gifted learners, add extra words or get learners to think of appropriate words. |

| Physics: lab reports The language of laboratory reports, which uses a lot of passive forms, is sometimes difficult for CLIL learners. This noticing task guides them to look at the passive tenses in an authentic laboratory report. Instructions Laboratory reports are often written in the passive tense (e.g. The test tube was filled, The liquid was measured out), to make them more formal and less personal. You can recognise passive-voice expressions because the verb phrase always includes a form of be, such as am, is, was, were, are, or been. However, the presence of a form of be does not necessarily mean that the sentence is in the passive voice. You can also recognise passive-voice sentences since they often include a ‘by the...’ phrase after the verb, for example The man was bitten by the dog). Here is a part of a real laboratory report. Underline all the examples of the passive tense in the text. How many are there? The spring we tested was a coil spring from the rear suspension of a 1968 Volvo sedan (model 142s). It was a left-hand helical compression spring, had open ground ends, and was made of steel. The dimensions of the unloaded spring, the outside diameter, the total number of coils of turns and the wire diameter are listed in Table 1. Using these dimensions, the spring’s fully compressed length (solid height) was estimated to be xx cm, or -xx% of its free length. This estimate was based on the following equation [...] where NT is the total number of coils, L0 its free length and d is the diameter of the wire. This value was used to specify the maximum compression which was used in the test. Setting this value at xx%, an estimate of the forces that would be generated was also made using the following equation where x is the deflection of the spring, N=L0/NT is the number of active coils, D is the mean coil diameter and G is the shear modulus for the spring material. |

34. Rabking cards#

| List items related to a topic in order of importance. |

| This activity works well for a revision lesson or at the end of a series of lessons on a topic; the learners need to know something about the topic before you start. Individual work Learners or the teacher first write down ideas, concepts or facts about the topic individually; each of these must be written on a different card. Learners then mix up their sets of cards and spread them on the table face down. They then select two cards at random and discuss which is the most important. They put this one on the left. Learners then take a third card and compare it with the card on the right, asking the question Which of the two is more important? They place it on the appropriate side and continue until their cards are used up, thus creating a row of cards with the most important idea on the left, and the least important idea on the right. Pair work Once both learners have constructed their own lists, ask them to compare the lists and construct a new, combined list using the same procedure. |

| History: the Industrial Revolution Per card, learners write down one invention made during the industrial revolution (for example: flying shuttle, spinning jenny, spinning mule, cotton gin). They then rank them, answering the question Which of these inventions has had the greatest impact on people’s lives and why? |

35. Jigsaw reading#

| Different learners read different information, then exchange the information. |

This task works well with a text which can be divided into 3-5 sections, each of which contains separate information about the same topic.

|

| History: the Reformation This is an example (based on Walsh, 2004) of learners becoming experts on one part of the course book unit about the Reformation. The teacher divided the unit into sections and the class into groups. Each group was given different questions to answer or tasks to do: Group 1: pages 30 and 31: ‘Medieval reformers’ Make a list of concerns about the Roman Catholic Church during the Middle Ages. What made the spreading of new ideas about the Church easier? Group 2: pages 34 and 35: ‘Luther’ Make a list of the events which happened between the time of Pope Leo X and Luther.Make a list of events which happened between the time of Emperor Charles V and Luther. Why did the ruler of Saxony support Luther? Which role did propaganda play in the struggle between the Pope and the Emperor on one side and Luther on the other side? Group 3: pages 36 and 37: ‘The Protestant Reformation: Europe divides’ Look at the map on page 37: To which country did the Netherlands belong? What was the main religion in the Netherlands? What can you say about the size of the Netherlands during the 16th century? Group 4: page 36: ‘Protestant Europe’ Who were more attracted to Protestant ideas? Why were they more attracted to these ideas? Make a table in which you give information about the two groups of Protestants: Lutherans and Calvinists. Group 5: pages 38-39: ‘The Pope strikes back: The Catholic Reformation’ Why did the Pope call for the Council of Trent? List the main points from the Council of Trent. What was the Inquisition? What was the consequence of the Council of Trent? After they had answered the questions in groups, the groups exchanged information. Then, five new groups were formed, each containing one expert on a different section. The new groups had to create a summary of the whole chapter, answering the questions, “Who were the most important people during the Reformation, and what were the most important events?” |

36. Graphic organisers#

| Learners organise information on paper. |

| A graphic organiser is a visual representation of information. It can be used to help learners manipulate - understand or transform - information into another form. For example, a tree map can help to categorise information, a bubble diagram to show sub-topics within a main one, a Venn diagram to compare and contrast, a time line to put events in chronological order. Observation, listening and reading guides are types of graphic organisers: they help learners to organise or change information. |

| All subjects - Give learners empty or half-completed graphic organisers, and ask them to complete them during reading or listening tasks. Differentiate by giving quicker learners an empty graphic organiser and slower learners a half-completed one. |

| History: timeline Create a timeline using the Teach-nology website and ask learners to complete it: www.teach-nology.com/web_tools/materials/timelines History: concept map Concept maps work well to help understand complex ideas. Write the concept (e.g. Imperialism) in the middle of the map and ask the learners to complete the rest.  |

37. Stickers#

| Play a sticker game related to difficult concepts. |

This fun activity interests a class in (less exciting) material and is useful for revising difficult concepts.

|

Biology: hormones

Questions learners can ask each other: “Am I a hormone?” “Am I related to pregnancy?” “Do I function in the kidney?” As a second step, learners can stick their labels on the board, after which a few learners create a mind map with all the concepts. |

PRACTICAL LESSON IDEAS – ENCOURAGING OUTPUT #

38. Hot air balloon debate#

| Have a ‘balloon debate’ to decide who deserves to be saved from a sticky situation. |

| Learners imagine they are in a hot air balloon which is losing helium and height and will soon crash because it is too heavy. Each passenger has an opportunity to make a speech outlining the reasons why s/he should be allowed to remain in the balloon. The audience decides which of the speakers has presented their case most persuasively. Divide the class into a number of teams, each representing one passenger in the rapidly descend- ing balloon. In these groups, the learners prepare to present their case about why they should stay in the hot air balloon. They can write short notes to help them remember what to say, but the speech should sound as spontaneous as possible. This preparation stage can also be given as homework. Once the preparation has been completed, to ensure that everyone in the group contributes, randomly appoint the first contestants to give the speech from each group. You may want to provide learners with a scaffold or some questions to help them to prepare their speeches. You could also give learners guidelines for structuring the presentation of their arguments, such as:

After each group’s first speech, the class votes for the two most convincing characters. Learners are not allowed to vote for their own group! The two remaining survivors give a new speech, summing up the crucial reasons, and trying to add new ones, for their continued survival. Finally the class votes for the last remaining survivor. This link lists websites on debate rules: www.educationworld.com/a_lesson/lesson/lesson304b.shtml. This link gives examples of balloon debates: www.kent.ac.uk/careers/interviews/balloonDebate.htm |

| History: The Russian Revolution Carry out the hot balloon debate with five historical figures related to the Russian Revolution: Tsar Nicolas II, Karl Marx, Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin. |

| Variation: Chain debate Preparation The teacher makes two smaller groups, Group 1 and Group 2. The teacher writes down a controver- sial statement. Group 1 must agree with the statement and Group 2 disagree. The rest of the class are members of the jury who will decide which learner has used the most convincing arguments and thus wins the chain debate. The two groups first prepare a number of arguments for (Group 1) or against (Group 2) the statement. They will need the same number of arguments as there are people in their group: every learner argues a single point during the debate. The debate

|

39. The controversial questions#

| Agree or disagree with a controversial statement. |

| Learners think individually about a controversial question. First, they spend a couple of minutes thinking for themselves and writing down their views. Then the teacher allocates buzz groups that are given five minutes to discuss their view on the question and to come up with an answer and an explanation. After five minutes the teacher asks one learner per group to give an answer. |

| History: Solving global problems. ‘Is the UN an outdated organisation?’ Physical education: Doping is difficult to trace. Should athletes therefore be allowed to use doping? |

40. Role-play#

| Learners change input into a role-play. |

| Learners create a role-play after, for example, watching a DVD clip, reading a text, or doing a task. |

| History: Elizabeth I of England Show the film Elizabeth. As they watch, half of the learners prepare to be Queen Elizabeth I. The other half is given one of these names and prepares to play him or her:

To find out the answer to this question, the learners walk around the classroom. The “Elizabeths” ask as many people as possible questions to find as many allies as possible. In the follow-up plenary, the class has a new task: the learners who were Elizabeth place the other characters into two groups: allies or enemies. Then the Elizabeths explain their reasons and choices. Biology: menstruation game Give the learners the task to act out the menstruation cycle. Each learner plays a different part of the body and explains their role. This is a creative way of recycling information. |

41. Taboo guessin game#

| Describe a key word so that other learners guess what it is. | ||||

| Divide the class into teams of three or four. Two groups compete against each other. Each has a clue giver and a checker. Team A’s clue-giver turns over the first card and holds it in his hand so only he and the checker from Team B can read it. The clue-giver describes the mystery word at the very top of the card without using any of the taboo words printed below it. No rhyming words, hand motions or sound effects may be used. If the clue-giver from Team A says one of the taboo words, the checker from Team B will say ‘taboo’ and a new card is turned over. The group must guess the word within 75 seconds. | ||||

| Scoring Each time a team guesses a word correctly within 75 seconds, their team scores a point and a new card is turned over. If the clue-giver says one of the taboo words or runs out of time, the team loses a point. | ||||

| Biology: Species | ||||

| Mystery word | den | predator | mammals | habitat |

| Taboo words | bear home nest fox shelter | prey kill eat hunt animal | fur hair milk animals humans | food environment home shelter water |

42. Elevator picth#

| Sell an idea in two minutes. |

| An elevator pitch is a concise, carefully planned, and well-practised description that anyone should be able to understand in the time it would take to ride up an elevator. An elevator pitch could be held in almost any subject. Learners prepare a short persuasive talk of no more than two minutes about a subject-specific topic, object or process. In this talk, they describe the specific features of the topic and convince their fellow classmates of the benefits or advantages of their choice. Their talk is a kind of commercial, and learners need to make sure their fellow learners will vote for their ‘elevating idea’. |

| Art and design: the best painting Learners choose a piece of art and present an elevator pitch to convince their fellow classmates that the painting they have chosen is the best of its kind. Other learners vote for the best performance and give reasons why they have selected one particular elevator pitch as best. |

| Variation Alternatively, to encourage learners to read articles about art on a more regular basis, organise short presentations at the beginning of each class. Ask different learners at the end of each class to find an interesting article on art and to summarise it for the other learners during the next class, including an explanation of why they chose the article. This can lead to interesting discussions about art. |

43. Government economies#

| Debate about the abolition of an object, organisation or system. |

| Provide information related to the possibility of abolishing something, for example an organisation, an object, a religion, or even a chemical. Learners now form small groups to discuss arguments for and against abolishing their object or organisation. The outcome of these talks will be discussed in a plenary session. |

| Biology: Human organs The government has announced plans to economise on the costs of human bodies. The most striking measure is the plan to abolish at least one entire organ system. However, there is still no consensus among government officials which organ system should be done away with. According to reliable sources, more details will be announced next month. The different organisations for organ systems have been asked for input and comment. The following seven institutes were approached:

The following procedure has been proposed. Each of the organisations will send representatives to argue their case to keep their particular organ system. The talks which will be held at school. There will be simultaneous meetings, each with one representative of each interest group. The outcomes will be discussed in a plenary session. Hopefully, a government official will be present to witness the possible consequences of their proposed policies. |

44. Information gap#

| Ask questions to find the missing information. |

| Give learners different texts about the same topic which contain different information and some gaps where information is missing. Using their texts, learners prepare questions for each other, aiming to find out the missing information. Then, learners ask and answer each other’s questions. |

| History: Egyptian scripts and the Rosetta Stone Source Show learners Egyptian hieroglyphs. Learners first discuss in pairs what they know about ancient Egyptian scripts. If they do not know anything about the topic, ask them to write down their questions. Divide the class into two groups, A and B. Explain that they will receive two texts about the Rosetta Stone, but that some information is missing. In pairs they will ask each other questions to try and complete the text. Give them time to read the text and prepare questions to complete their own gaps. When they have written their questions, tell them to take turns to ask questions and write the answers in the appropriate gap on their worksheet. |

| Variation Alternatively, to encourage learners to read articles about art on a more regular basis, organise short presentations at the beginning of each class. Ask different learners at the end of each class to find an interesting article on art and to summarise it for the other learners during the next class, including an explanation of why they chose the article. This can lead to interesting discussions about art. Group A - What is the Rosetta Stone? The Rosetta Stone is a stone with writing on it in two languages (1 ____________________ + 2 ____________________), using three scripts (Hieroglyphics, Demotic and Greek). The Rosetta Stone is written in three scripts because when it was written, there were three scripts being used in Egypt. The first was Hieroglyphics, which was the script used for 3 ____________________ documents. The second was Demotic, which was the 4 ____________________ of Egypt. The third was Greek, which was the 5 ____________________ at that time. The Rosetta Stone was written in all three scripts so that the priests, government officials and rulers of Egypt could read what it said. The Rosetta Stone was carved in 6 ____________________. The Rosetta Stone was found in a small village in the Delta called 7 ____________________ in 1799 by French soldiers who were rebuilding a fort in Egypt. It is called the Rosetta Stone because it was discovered in a town called 8 ____________________. Group B - What is the Rosetta Stone? The Rosetta Stone is a stone with writing on it in two languages (Egyptian and Greek), using three scripts (1___________________ + 2___________________ + 3___________________). The Rosetta Stone is written in three scripts because when it was written, there were three scripts being used in Egypt. The first was 4___________________, which was the script, which was the common script of Egypt. The third was 6 ___________________, which was the language of the rulers of Egypt at that used for important or religious documents. The second was 5 ___________________ time. The Rosetta Stone was written in all three scripts so that the priests, government officials and rulers of Egypt could read what it said. The Rosetta Stone was carved in 196 B.C. The Rosetta Stone was found in a small village in the Delta called Rosetta in 7 ___________________ by 8 ___________________ who were rebuilding a fort in Egypt. It is called the Rosetta Stone because it was discovered in a town called Rosetta. |

| Variation To check that learners have understood the texts, you can design a task for them based on the information from the two texts. This task should be impossible to complete without the missing information that the other learner has. Geography: Jigsaw puzzle Jigsaw tasks are tasks where several learners are given parts of the information needed to complete a task. They need to ask each other questions to complete the ‘puzzle’. In pairs, learners each receive a partially completed chart giving different information about three countries. Without looking at each other’s chart, both learners request and supply missing information to complete their charts. |

45. Talking about talking#

| Help learners understand and discuss what useful ‘exploratory talk’ is when doing group work. | |||

| Have a short plenary discussion about working in groups and what kind of questioning or feed- back helps the group to work together. Introduce the term ‘exploratory talk’: people work critically but constructively with each other’s ideas. Write some of the points the learners make on the board. Next, give each learner a copy of the Exploratory talk handout below. Each learner completes the handout individually. Once everyone has finished, hold a small group or class discussion on the results. At the end of the activity, come up with some key points which are important to keep in mind when doing group work. This activity can be used in all subjects. | |||

| Exploratory talk Below are some suggestions which might help or hinder your group to work with and talk to each other. Read the suggestion in the left-hand column. Tick the ‘helpful’ or ’unhelpful’ column first, then note down what particular effects you believe the contribution might have in the right-hand column. | |||

| Contributions | Effects | ||

| Bringing new ideas into the group | |||

| Saying, “Yes, but...” | |||

| Summarising an idea that a group member has just suggested | |||

| Arguing about an idea | |||

| Asking questions | |||

| Suggesting another idea related to one just mentioned | |||

| Giving your own point of view | |||

| Write your own helpful idea here (in the -ing form): | |||

| Write your own less helpful idea here (in the -ing form): | |||

46. I am a#

| Write about a process in the first person. |

| Ask learners to write a story in the first person about a process in your subject. They explain what happens in the various stages of this particular system. The learners imagine they are part of an enormous system and that they are going on a journey through that system. Whether they survive or not, a report must be written in which learners describe what happens at every stage of their journey: which of their friends they encounter or lose at each stage. Create a handout for them like the one below. Make sure your learners know what to include in the story and how to structure it: where does it takes place, what challenges must the character face and overcome, how does the character reach their final destination (or not!). They should tell their journey as a narrative, starting at the beginning of the process and finishing at the end. |

| Biology: Digestive system Imagine you are part of an enormous cheeseburger. Perhaps you are the bread roll, or the melted cheese, the pickles, the onions, the secret sauce, the lettuce or possibly even the beef. Whatever part you choose to be, you are the leader. It is your mission to lead the burger on a dangerous journey. A journey to the bottom of the world. A journey through the digestive system. It is a journey involving many risks and not all of you will survive. All of you will come under attack and most of you will be destroyed along the way. Many of you will suffer a painful death and be broken down into many thousands of pieces, to be absorbed into the blood of a voracious monster otherwise known as Homo sapiens! Whether you survive or not, a report must be written for base headquarters. In the report you must describe what happens at every stage of your journey. Say which of your friends (food types/ nutrients) is destroyed at each stage and who is responsible (yes, watch out for the vicious enzymes and evil acid!). Tell it as a story, starting in the mouth and ending in the anus. At the end, only one of your friends is left over... let this ‘person’ take over the story after you have been destroyed. |

| Variations Geography: The journey of lava in an exploding volcano. Biology: The journey of a migratory bird or animal. Physics: The journey of a carbon atom. History: The journey of a soldier’s tiffin tin (lunch box) in the trenches. |

47. The story of ...#

| Write about a process in the third person. |

| Ask learners to write and illustrate a 300-word children’s story in the third person about an object, describing what happens to the object when it is being transported from one place to another. In their story, learners describe: specific details of the object; its origin; and in detail, its journey from departure to arrival. Their account should read as a children’s story, beginning with an introduction (who or what is this object), a middle (the actual journey with all sorts of events, unexpected hazards) and an ending (end of the journey, where the object is now and what has happened to its shape). Provide some scaffolding to help them to plan and write their story. |

| Geography: Erosion and river processes 1. Plan your story by answering these questions.

3. Write a rough draft of your story in your notebook and edit it. If you work on the computer, always print out your work and bring it to class. If you do not do so, you will be wasting your class time. 4. Hand in a final copy including the sketches, drawings or pictures. |

| Variations Technology: The journey of raw materials across the globe; for example, from cotton plants to jeans, or from coffee plantation to a coffee bar in New York. History: The journey of a captured flag during war time. Biology: The journey of a hormone, a red blood cell or an egg cell. |

48. Dictogloss#

| Dictogloss: reproduce a short text you have listened to. |

| Learners listen to an audio text about a topic. They eventually need to reconstruct the text in as much detail as possible. In doing so, learners practise listening, writing and speaking, and use vocabulary and grammar to complete the task. The learners listen to your chosen text, read along at normal speed, and write down key words. Then, in groups of three or four, they work closely together to share, compare and discuss their individual notes and co-operate to reconstruct the text in as much detail as they can. |

| History: The Aztecs 1. Using a course book or the Internet, find a short text on the Aztecs of no more than ten sentences.

3. Reconstruction: The learners work in pairs and then fours to compare notes and write a shared version of the text, editing for accurate punctuation, spelling and inclusion of the main ideas. 4. Analysis and correction: The learners compare reconstructions with other groups and with the original. Discuss the differences. |

49. Dictogloss#

| Develop a sketch and describe a process in the third person. |

| Provide learners with a series of basic sketches that represent a process you have covered in your recent lessons but in which certain steps have been left out. Learners add information (colour and details) to each sketch to show the steps in the process. They also write a descriptive text for each drawing. |

| Geography: The development of tourism in the Alps The learners are given three pictures of an Alpine valley on A3 paper, entitled:

|

| Variations History: Working conditions for farmers or industrial workers in Europe. Physical education: Different stages of the high jump. |

50. What has just happened#

| Reconstruct a table with missing information. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ask learners to reconstruct something that is damaged or broken, by doing an experiment.Then, ask them to write a report on how they carried out this investigation. In the report, learners describe their research method and give reasons for choosing this method. They write in the style of a police report, explaining in detail the various stages of the investigation, giving a detailed analysis of the research, and drawing a well-argued conclusion. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Science: Density measurements Learner handout In the box at the front of the classroom you will find a set of nine different objects used for various scientific experiments. Originally, the box came with a small card which described the composition of the objects. However, someone has damaged the card, and now it can’t be read any more.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The aim of this exercise is to identify the materials from which the objects have been made and to make a new table to replace the damaged one. To perform the investigation you will need to make density measurements of the objects. Density measurements can be obtained by measuring an object’s volume and mass. You will have to make some choices, such as what equipment to use and what formulae you might need. Choose wisely – your decisions will affect how accurate you can be and how precisely you can identify the materials! Different objects may require different solutions, so don’t be afraid to make new choices each time. Carry out appropriate measurements to find density and record the results in a new table. Describe your methods in your notebook. Perform more measurements to check for floating, magnetism and electric current. Fill in the table. The data you collected will not be enough to identify the composition of the objects. For this, you will have to compare your values with those from a reliable source. Data from such a source will be displayed in the classroom. How do your values compare with the benchmark? How sure can you be about your identifications? With your partner, write a report. In it, describe how you carried out the investigation and try give valid reasons for choosing your methods. Include a completed results table identifying the objects. You can work together, but you must hand in one report each. Give yourselves a score (out of 10) indicating how confident you are of the identifications. Explain why you give yourself the score you do! |

51. Learner-generated questions#

| Create your own difficult questions and talk about questions. | ||||

| Stage 1 You will need a classroom cleared of chairs or a gym or hall. Give the learners one coloured card each. Use a page from your course book which is challenging for your class; there should be quite a bit of information on the page. Remind learners of English question words such as what, when, why, how, where, and how many. Tell the class you are going to practise asking difficult questions.Each learner thinks of a difficult question about the course book page and writes it down on his/ her card. Then everybody stands up and circulates, asking and answering the questions. When the learners have run out of energy, ask them to sit down again for the discussion which follows. Stage 2 Carry out a class discussion about content and language, asking questions like:

History: The Holy Roman Empire

| ||||

| Variations Collect all the questions and use a number of them in a test on the material. |

52. A day in the life of ...#

| Write the story of an event from the point of view of a person who experienced it. |

| Learners write a story (with a minimum of one page) in the first person about a special event or day in the life of a particular person from your subject. They describe specific details about this person, and what a day in the life of this person could look like. |

| History: Ancient Greece Imagine you are living in Athens. Who are you? A woman, a male citizen or a slave? You are going to write about a day in your life. Perhaps there is a special event you are going to attend. Or you could write an autobiography: write about your childhood, your parents or what you are doing right now in Athens. When choosing your character, please answer the following questions: If you are a female citizen: Are you married or not? Do you live in a wealthy or poor household? How does your family earn its money? How do you spend your time each day?If you are a male citizen: Are you married or not? Are you wealthy or poor? What goes on at the debates in the assembly? Have you served in the army? If you are a slave: Are you male or female? Are you young or old? Who owns you: a family or the state? Where were you born: in Athens or somewhere else in Greece, or in a different country? How did you come to be a slave? What job do you do? Your story should be a minimum of one page (A4; typed). It will be assessed on the use of English, the historical content, layout and originality. |

| Variations Geography: Imagine you are an Indian living in the Brazilian rainforests. Biology: Imagine you are a human organ. Physical education: Imagine you are a famous footballer/hockey player. |

53. Class magazine#

| Write a magazine about subject-specific issues. |

| Learners compile a complete magazine for their peers about a topic you are covering. It is a class assignment, and each group will be awarded a mark for their contribution. Good organisation is an important part of the assignment, and this will also be taken into account. |

| Biology: Class magazine on drugs and alcohol Ask learners to make groups of three. One of these groups will comprise the editing team and co-ordinate the gathering of articles and lay-out of the magazine. The editors don’t have to write any articles about drugs and alcohol, but they have a number of other responsibilities. What does the editing team have to do? What does the editing team have to do? |

|

54. Encyclopaedia entry#

| Write an entry for a children’s encyclopaedia. |

| Ask learners to design an entry for a children’s encyclopaedia about different aspects of a topic you are covering. First, look at Wikipedia or another encyclopaedia for models. Discuss the difference between a children’s and an adult’s encyclopaedia. |

| Geography: Population density Learners write an encyclopaedia entry about a country’s population density. Provide some pointers to help them prepare. For example:

|

55. Design a model to be tested in class#

| Non-linguistic process. |

| Ask learners to make a subject-specific topic design and model, which will also be tested. |

| Technology: Design a model In this exercise, learners are civil engineers. They design and make a scale model of a new bridge. The scale model should meet the following requirements:

Design a “mousetrap car” that drives as far as possible. Make a work plan with

Science: Make an electric circuit. Chemistry: Make a model of a molecule. Biology: Build a part of a human skeleton and name the major bones. |

PRACTICAL LESSON IDEAS – ASSESSMENT AND FEEDBACK #

56. Name and assess the content and language used in activities#

| Describe and assess speaking and/or writing aims related to assessments in your subject. | ||

| When you set an assessment, tell the learners both the subject focus and the language focus of the activity. Explain the language focus for speaking or writing and tell the learners you will assess both the content and how they use language to achieve the speaking or writing task. | ||

| Geography: Globalisation Show learners how the assessment, content and language aims are linked by putting them on the board when you set the assignment: | ||

| Assessment How does globalisation affect people at a local level, and what happens if the economic chain is broken? Write a report for a local newspaper, or record a programme for local radio. | Geography focus Identify effects of globalisation on factory workers and explore the impact of a break in the chain on individuals and the industry. | Language focus Write using a report genre, or devise a radio report and tape in groups of two or three. |

| Variation Geography: scale and geographical analysis Geography: scale and geographical analysis

| ||

57. Task with language and subject assessment criteria#

| Assess in a task instead of a test and provide explicit marking criteria for both subject and language. |

| Use a checklist to design an assessment task, rather than a pen-and-paper or digital test. Include language and subject assessment criteria when you give the checklist to learners. |

Checklist:

|

| Biology: Classification These answers are based on the poem poster in Example 31.

|

58. Assessment questions#

| Learners answer questions about their assessment before submitting it. |

Write your assessment criteria in the form of yes/no questions to your learners. Give them the questions at the same time as you give the task so that they think more actively about what they have to do. The questions will vary according to the task you set. Here are some example questions which learners can answer to check they have completed a task properly, based on the geography example below.

Assessment task: decision-making exerciseThe problem A large area of land in the Brazilian rainforest is in need of redevelopment. There is, however, disagreement about which method of redevelopment would be most appropriate.Your role Your group are representatives of the Kayapo Indians, the Government, or the WWF.Your task

Your work will be assessed according to the following questions:

|

59. Rubricks#

| Making assessment criteria transparent. |

| Preparation You will need a copy of an assignment or project for your learners on paper and an empty rubric (see Example 32 and 33). 1. Discuss the assignment or project. Work with a colleague or colleagues (subject and language teachers) or learners, to clarify subject and language aims. 2. Brainstorm together to produce a first version of the assessment criteria. Accept all ideas at this stage. For example, here are some brainstormed criteria for a history presentation to a German commandant on how the use of gas in the First World War can be justified: Possible subject criteria Clear introduction Accurate information (dates, events) Complete information on how gas was used and by whom Reasons why the use of gas can be justified Reasons why its use cannot be justified Clear conclusion ... Possible language criteria for speaking Pronunciation, intonation, word stress, grammatical accuracy grammatical range, vocabulary range, use of linking words, fluency, use of language of persuasion, ... Possible presentation criteria Attention-grabbing start Visuals support points Visuals support points Eye contact Body language Audience awareness Amount of text on PowerPoint slides... 3. From the brainstorm, select five to eight criteria, so that the rubric fits on one page. Write them in the left-hand column. 4. Write descriptors (short descriptions) in the boxes. Start with column 4, the best achievement, and work backwards. Be as specific and positive as possible: write what IS true as far as possible, rather than what is not. A useful technique for writing descriptors is to use the phrases 4. yes ; 3. yes, but; 2. no, but; 1. no while writing each category. For example if the criterion is species information: level 4: Yes, species information is complete and correct level 3: Yes, the species information is correct, but it is not complete level 2: No, the species information is not all correct, but some of it is level 1: No, the species information is not correct at all 5. Share the first draft with other colleagues or another group of learners and ask them to give feedback on its clarity. You could also try assessing some assignments with it, if available. Discuss how clear and useful the criteria are. 6. Revise and improve the rubric. Make any changes you feel are necessary based on the feedback and your own experiences in the try-out. |

60. Gigh or low demands#

| Using Cummins’ Quadrants to balance cognitive and contextual demands. |

| Design an assessment which would fit into each of Cummin’s quadrants. Use this to design assessments which vary the cognitive and contextual demands you make on learners across the years. |

| Geography: Development of a waterfall Quadrant 1 Label Provide diagrams of the two stages in the development of a waterfall, with a list of terms. Ask learners to draw an arrow from each term to the correct place on the diagram. Quadrant 2 Reproduce information from a text Give learners a text on waterfalls and ask them to write down their answers to written questions on the text. Quadrant 3 Transform and personalise Ask learners to draw a diagram and explain the two stages in the development of a waterfall for a tourist brochure for a well-known waterfall. Quadrant 4 Argue a case using evidence Ask learners to write an article for a local newspaper, arguing against placing a pipeline in a waterfall. |

61. Relay race labelling#

| Assessing kinaesthetically. |

| Make four large, clear drawings of a picture you would like your pupils to label. You will also need 4 marker pens. Pin the drawings to the wall on the other side of the room. Make four teams. Teams stand at one end of the room; the drawings are at the other end. Teams have a pile of word cards (the labels for the picture). They send one member of the team at a time to label the drawing; learners are only allowed to complete one label at a time. Teams receive points for the number for labels they accurately place in a fixed amount of time. This can count towards their final grade at the end of term. |

| Physical education: Parts of the body Use a picture of the human body and ask learners to label the different parts. Picture and labels can be found on www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/anatomy/body/label/ |

62. Inner / outer circle#

| Sit in two circles and answer questions about a topic. |

| Create two parallel circles of equal numbers of learners (e.g. five in the inner circle and five in the outer circle), facing each other. Tell the learners they are going to have a test. They will revise together, and then take the test individually. Tell them the topic of the assessment. Show a question on the topic, which they discuss with the learner opposite them. Then say: outer circle move one person/two people to the left, so that they are then facing a new partner. Call out a second question which they discuss with their new partner. Call out: inner circle move two people to the left, and call out your third question. After all the questions have been asked and discussed, give the learners the questions in writing and allow them to write down their answers. Grade as a test. |

| Physical education: Parts of the body Use a picture of the human body and ask learners to label the different parts. Picture and labels can be found on www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/anatomy/body/label/ |

63. Correction code#

| Give feedback selectively. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use a correction code to give feedback on learners’ language. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History: First World War Learners have written a letter from a soldier in the trenches to his family at home. Chemistry: Diamond Learners have written their answer to one of the summative questions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sp Prep | In diamond, each carbon atom form four covalent bonds with ohtercarbon atoms. The carbon atoms around each other are tetrahedrally arranged. The network by carbon atoms extends almost unbroken throughout the whole structure. The regularity arrangement of the atoms gives diamond a crystalline structure. | TWO | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WF | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Variation There are many different possible correction codes. Here is an example of the most common codes used for correcting English. The most effective code is one which is designed and then used by all the teachers and learners together. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

64. Common mistakes#

| Identify and correct common mistakes. | ||

| Draw up a list of mistakes that learners often make in their writing or speaking for your subject. Put them in a table, and ask learners to identify the type of mistake and then correct it. | ||

| History: The French Revolution Common mistakes | Type of mistake | Correct sentence |

| The revelation started in 1789. | ||

| The revolution has started in 1789. | ||

| The revolution in 1789 started. | ||

| The revalution started in 1789. | ||

| The Revolution started in 1789. | ||

| The revolution started in the 1789. | ||

| The revolution which started was 1789. | ||

| The revolution started 1789. | ||

| The revolution kicked off in 1789. | ||

65. Card game with typical mistakes#

| Learners play a card game correcting typical mistakes. | |